What does the word “Hanukkah” mean? For children, it often means the holiday of presents. For Tel Aviv doughnut obsessives, it means congregating on all eight days at bakeries with the most elaborate sufganiyot. For many around the world, it’s “the Festival of Lights,” when seeing menorahs in the windows of neighbors’ homes illuminates the darkness. Hanukkah, with its connotation of triumph over stronger enemies, has been a source of hope throughout the centuries. But what’s most fascinating about Hanukkah is not its connotation but its roots, both historical and linguistic.

The holiday itself commemorates a revolt. In the year 168 BCE, the Temple in Jerusalem was desecrated and renamed for the Greek god Zeus. Antiochus had outlawed Judaism, banning the observance of Shabbat and holidays. He set up altars to Greek gods in the Temple, and gave Jews a choice that unfortunately would become familiar in future centuries: Convert or die. The Maccabees decided to resist instead — and won, despite facing overwhelming odds.

Keeping Hanukkah and lighting its lights became an act of defiance in later centuries — as the famous photo of a Hanukkah menorah in a window facing a swastika attests. But the dictionary meaning of the word, according to Even-Shoshan, the venerable Hebrew-Hebrew dictionary, is more utilitarian: simply the dedication of an object for its task, the opening ceremony or the first use of something in a new home.

“Hanukkah,” defined in one word, is “dedication.” Or more elaborately, for the holiday’s namesake — “the re-dedication of the Temple as a temple.”

I admit that I never thought about what the word means, because it was so familiar. The word is all over the Psalms, but it usually appears in the construct form: chanukat, or “the dedication of.” For English readers, this word, chanukat, is difficult to discern, simply because it is often translated as “dedication.” It’s probably impossible to hear how that is connected to the Hebrew word Hanukkah in the construct form, which means a noun attached to the following noun. Every noun in Hebrew has four forms — singular, plural, construct singular and construct plural.

Consider the opening of the 30th Psalm. In Hebrew, Psalms 30:1 reads mizmor shir chanukat habayit l’David. In the 1985 Jewish Publication Society translation, it reads: “A Psalm of David. A song for the dedication of the House.”

Without Hebrew knowledge, it’s hard to guess that “dedication” is chanukat, and there is no footnote to hint at it. It’s impossible to know that this is a construct noun situation. Yet this chanukat habayit, or “dedication of the House (Temple)” phrasing, is repeated throughout the Psalms — and since many psalms are part of daily prayers, this phrase appears in the prayers, too.

But what about the word Hanukkah, as a regular noun? That is also biblical. The word Hanukkah alone appears in Nehemia 12:27. According to the Jewish Publication Society translation, “And at the dedication of the wall of Jerusalem they sought the Levites out of all their places, to bring them to Jerusalem, to keep the dedication with gladness, both with thanksgivings, and with singing, with cymbals, psalteries, and with harps.”

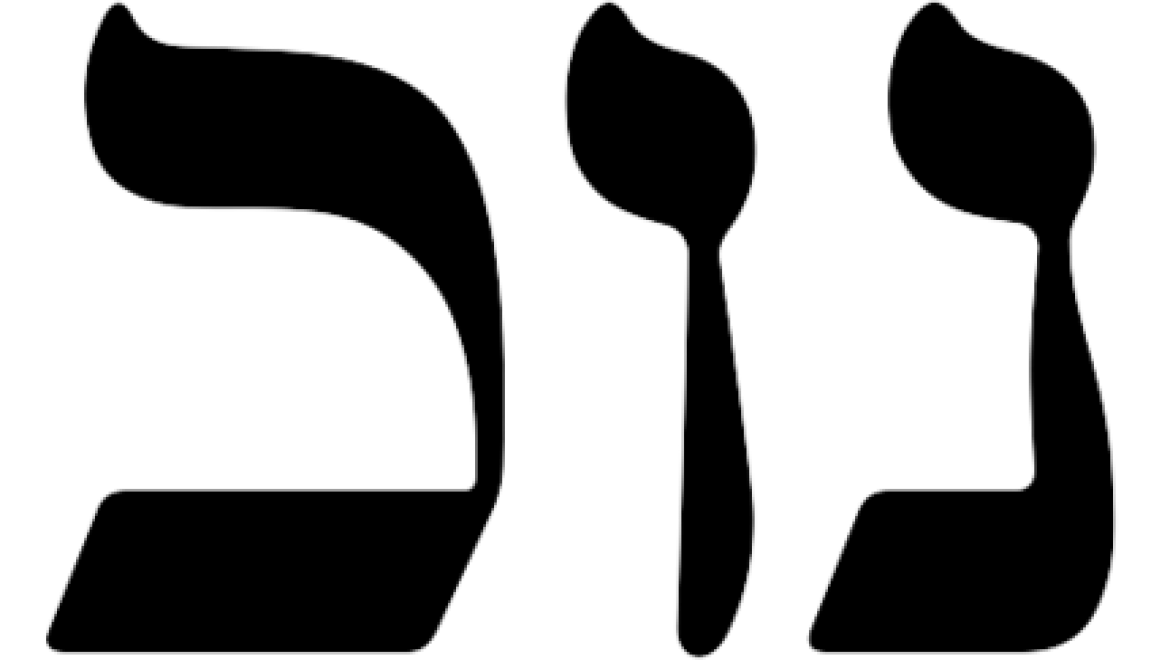

What is especially fascinating about Hanukkah is not its appearance in the Bible or the prayers, but the roots of the word. Hebrew, after all, is a language made of triliteral roots; Hanukkah is constructed from the three-letter root chet, nun, chaf, which also happens to be the root of words having to do with teaching and education.

But it extends past that. Hebrew theoretically assigns up to seven different structures for any given verb, each of which has a different meaning. All of them share a deep kernel of meaning, sometimes quite fascinating to discover. In this case, with the root chet, nun, chaf, one of these meanings is “to dedicate anew,” another is “to educate others,” and a third is “to educate oneself.”

L’hitchanech, or “to educate oneself,” is therefore linguistically related to the idea of using something for the first time and beginning to use something for what it is meant to be used as. Dedication and education share a root. And it’s a beautiful connection — to educate a child, after all, is the beginning of a child dedicating himself to his task, which is educating himself.

Ahad Ha’am, who famously wrote that more than the Jewish people has kept Shabbat, keeping Shabbat has kept the Jewish people, used the word nitchanech as he described the new generation of Jews — who he hoped would combine both modern freedoms and knowledge of the ancient. “The new generation, that was born and raised in freedom, and was educated (nitchanech) from youth on the knees of the great Torah,” Ahad Ha’am wrote.

Ahad Ha’am is on interesting terrain here, the terrain that the words nitchanech and Hanukkah — which share a root — both dwell in. The essence of the word Hanukkah — a dedication — is the ability of Judaism to continue. And historically, continuity has meant three elements: remembrance, education and resistance. These elements seem especially resonant this year, when history, knowledge, and the ability of the individual and society to stand up are all under attack.

Since the days of Antiochus in 168 BCE, Hanukkah has been about roots and holding on to them. We light to remember, to learn, and to honor resistance when who we are is threatened. And we light to dedicate ourselves, again, to the labor and responsibility of being free. This year, when calls to resist again punctuate the darkness, maybe the word we need to continue is Hanukkah.